On many occasions international organizations such as the UN, international agencies like the IEA (International Energy Agency) or working groups (the Africa Progress Panel, chaired by Kofi Annan, former Secretary General of the UN which had published a report on energy in Africa Power People Planet, in 2015, www.africaprogresspanel.org ) drew global attention to the strong energy inequalities existing in the world. In September 2015, under the auspices of the UN, 193 countries adopted a manifesto, the « Sustainable Development Goals », known as the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development. One of the 17 goals, the seventh, makes explicit reference to the need to ensure access to modern, safe, sustainable and financially accessible energy for all planet inhabitants. The UN highlighted the close relationship between energy and most of the world’s development goals, this Agenda for 2030, while emphasizing the need to increase the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix, has stressed the necessity of building energy infrastructures, developing technologies and doubling energy efficiency.

In its World Energy Outlook 2017 (IEA, Paris, November 2017, www.iea.org ), IEA recalls that access to modern energy is still a major challenge for many developing countries . Some figures show the extent of the problems to be solved, in 2016: – 1100 million inhabitants of the planet did not have yet access to electricity (14% of the world population), almost all of them being in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (85% in rural areas, around 600 million people in sub-Saharan Africa and 200 million in India), while access to electricity in some southern countries is often precarious (frequent power outages) – nearly 2.5 billion people used solid fuels (wood, straw, vegetable waste) for domestic tasks including cooking (120 million use kerosene and 170 million coal), often with rustic stoves (without chimneys), the air inside the houses is therefore highly polluted (especially by fine particles). In one hand while we observe a net but slow decrease in the population without electricity, on the other hand the number of inhabitants using polluting energies for cooking does not decrease (except in China where the population proportion using these energies has decreased by a third since the beginning of the century). The health consequences of this energy-related pollution are serious, with WHO estimating that it causes about 2.8 million premature deaths worldwide caused by respiratory diseases (women and children being most affected). It should be noted in passing that coal, apart from being the source of high CO2 emissions, is the main source of outdoor air pollution (see E.Gies, « The real cost of energy », Nature, vol.551, S145, 30 November 2007, www.nature.com).

For several years, the IEA has been examining the prospects for world energy with scenarios. One of them, dubbed « New Policies », takes into account the most recent national energy policy decisions (it would not achieve the objectives of CO2 emissions reduction compatible with those set at COP 21 in 2015). However, IEA observes in its 2017 report (although its scenarios are not « forecasts ») that by 2030, about 600 million people in the world would have gained access to electricity and 90 million more between 2030 and 2040. Thus, in 2030, 90% of the population of developing countries would be « electrified » (82% in 2016), the goal of the 2030 Agenda would not thus be fully achieved. It would be necessary to connect 92 million people with electricity each year, in one way or another, to achieve the 2030 Agenda objectives; Sub-Saharan Africa is still far from this goal (with the notable exception of Kenya, Ethiopia and South Africa), which is practically achieved in Asia thanks to the efforts of India and Indonesia. The ongoing urbanization of the planet, especially in developing countries, will be an important factor of electrification. According to the IEA, the prospects of eliminating the use of polluting energy for cooking remain « dark »: 1.9 billion inhabitants of the planet would still use it in 2040 (800 million in sub-Saharan Africa and almost 400 million in India). However, reducing the number of premature deaths due to these polluting energies would be significant (almost 500,000 fewer deaths in 2040 than today).

The IEA has updated a proactive scenario in its 2017 report, called « sustainable development »: its prospects for energy, by 2040, would be consistent with the objectives of the Paris climate agreement (limit to 2 ° C, and if possible at 1.5 ° C, the warming of the planet between the beginnings of the industrial age and the end of the century). It « predicts » a faster reduction in CO 2 emissions and air pollutants (notably nitrogen and sulfur oxides), and a greater increase in electricity in the global energy mix. This scenario would make it possible to reach the objectives of the UN 2030 Agenda: 1.3 billion inhabitants of the planet deprived of electricity, today, would have access to it in 2030 (taking into account the increase of the world’s population), twice as much as in the « New Politicies » scenario  and 2.9 billion households would have been provided with « clean » energies, there would be « only » 800,000 premature deaths due to air pollution in homes (but 2.5 million deaths due to outdoor air pollution). In this scenario, the share of renewable energies in the final energy mix (consumption) would be twice that recorded in 2016 (15%). On a global scale, the investments needed until 2030 to achieve an energy transition would be 15% higher in the « sustainable development » scenario than the basic one (“New policies”); in this proactive scenario, one would achieve universal access to modern energy in all developing countries in 2030 at a cost of 430 billion additional investments, an average of 30 billion per year more than in the basic one.

and 2.9 billion households would have been provided with « clean » energies, there would be « only » 800,000 premature deaths due to air pollution in homes (but 2.5 million deaths due to outdoor air pollution). In this scenario, the share of renewable energies in the final energy mix (consumption) would be twice that recorded in 2016 (15%). On a global scale, the investments needed until 2030 to achieve an energy transition would be 15% higher in the « sustainable development » scenario than the basic one (“New policies”); in this proactive scenario, one would achieve universal access to modern energy in all developing countries in 2030 at a cost of 430 billion additional investments, an average of 30 billion per year more than in the basic one.

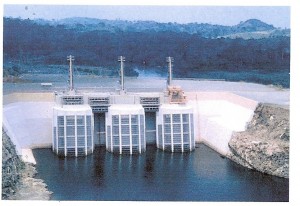

Techniques to ensure universal access to modern energy (electricity and « clean » heat for cooking) are available but need to be adapted to local situations. On one hand, one can observe that solutions to reduce the number of inhabitants of the planet without access to « clean » energy, and at the same time that of deaths directly related to the domestic use of polluting energies, are relatively simple and inexpensive: » modern » stoves with chimneys, use of liquefied gas (LPG), biogas, solar energy. Universal access to electricity, on the other hand, requires diversified solutions depending on whether it concerns urban or rural areas (see, P.Papon, 2050: quelles énergies pours nos enfants?, 2017, Le Pommier). Electricity generation in rural areas and small cities, which are not connected to an electricity grid, in Africa in particular, can be provided by renewable energies (solar, wind near coastal areas, possibly by mini-hydraulics, or even mini thermal power-plants powered by biogas or fuel connected to mini-grids. Urban areas, which are becoming increasingly important in developing countries, require greater power, and electricity supplied by intermittent renewable energies (especially solar) must be supplemented by hydroelectricity (which presupposes the construction of expensive electric lines) or electricity produced by gas-fired power plants. Urban areas, which are becoming increasingly important in developing countries, require greater power, and electricity supplied by intermittent renewable energies (especially solar) must be supplemented by hydroelectricity (which presupposes the construction of expensive electric lines) and electricity produced by gas-fired power plants.

Universal access to electricity will undoubtedly impose a transitional phase (the 2050 horizon?) and a diversified electricity mix. It should be noted that India, which is far from being fully electrified, has launched a very ambitious renewable energy development plan with the objective of setting up a new capacity of 175 GW by 2022 (100 GW of photovoltaic solar energy, 60 GW of wind, 10 GW of bioenergy and 5 GW of mini-hydro, see IEA World Energy Outlook 2017). Morocco has also launched a major plan for the development of solar energy (also implementing the sector of concentration, see the photo of the Ouarzazate power-plant).

GW of mini-hydro, see IEA World Energy Outlook 2017). Morocco has also launched a major plan for the development of solar energy (also implementing the sector of concentration, see the photo of the Ouarzazate power-plant).

Eliminating energy poverty in developing countries is a global challenge, addressing it is a response to the need to ensure equity and to help avoid international tensions in some regions of the world where there are significant development inequalities. IEA has calculated at least $ 50 billion per year would be necessary to insure universal access to modern energy in 2030. This effort is not out of reach because it represents only one thousandth of the world’s GDP. Kofi Annan, for its part, in his report on energy in Africa had estimated that $ 55 billion would be required in Africa to meet the electricity demand while ensuring universal electricity access (this would increase only slightly its global share of CO2 emissions, it would increase from 2% to 3% in 2040). IEA scenarios for the whole of Africa envisage a 2.5 multiplication factor for its  electricity production by 2040 (2000 TWh in 2040 against 800 TWh in 2016 but the quantification of the investments remains unclear). For example, the « Practical Action » organization, which deals with international development, has estimated that $ 5 billion would be needed for universal energy access to Togo alone (Poor People Energy Outlook 2017, www.policy.practicalaction.org/ policy. ../energy/poor-peoples-energy) Eradicating energy poverty requires both the mobilization of techniques, often available, and an ambitious financial engineering in order to find the necessary capital (especially through the African Development Bank in). International North-South cooperation, with transfer of technology, will be a catalyst to achieve this.

electricity production by 2040 (2000 TWh in 2040 against 800 TWh in 2016 but the quantification of the investments remains unclear). For example, the « Practical Action » organization, which deals with international development, has estimated that $ 5 billion would be needed for universal energy access to Togo alone (Poor People Energy Outlook 2017, www.policy.practicalaction.org/ policy. ../energy/poor-peoples-energy) Eradicating energy poverty requires both the mobilization of techniques, often available, and an ambitious financial engineering in order to find the necessary capital (especially through the African Development Bank in). International North-South cooperation, with transfer of technology, will be a catalyst to achieve this.